This week, Sir Ian Austin and the Telegraph were forced to apologise for a libellous opinion piece penned by Austin that commented on the outcome of the libel trial between Rachel Riley and former Labour staff Laura Murray. Just before Christmas last year, Nicklin had found in favour of Rachel Riley, awarding her £10,000 in damages.

Austin referred to the outcome of the trial to spit, without any foundation, to claim that Murray was an ‘anti-Jewish racist’ and part of the ‘vile anti-semitism of Corbyn’s Labour.’ Austin and the Telegraph have, as part of their apology, agreed to pay substantial damages.

Austin’s odious hit piece, which was liked and retweeted by a range of prominent right-wing Labour figures on Twitter, spoke to how profoundly misunderstood the Nicklin judgment was. It also illustrated how, in the anti-Semitism crisis in particular, libel law has been referred to and mobilised as part of a political project to attack the left in Britain on the flimsiest grounds.

Unfortunately, the damage of Nicklin’s judgment isn’t confined to people misunderstanding its content or how it was received by the Twitterati; the judgment, itself, is extremely concerning.

Indeed, Nicklin’s judgment was deeply and perplexingly flawed. Nicklin distorts logic in contorted brain-busting thinking in order to find Murray innocent of the facts but guilty in law. Most importantly, Nicklin’s judgment creates precedent that massively widens the application of libel law and will have a chilling impact on democracy. In a country where libel and lawfare is used to achieve political ends that cannot be achieved through the normal cut and thrust of political debate, this is a grave threat.

The Allegation of Libel

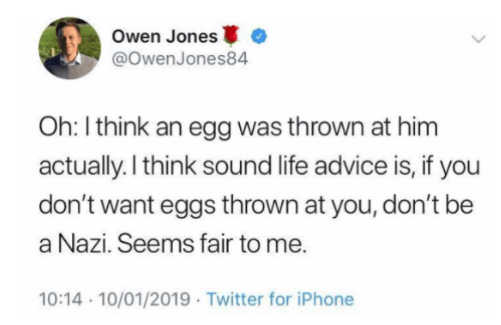

The case brought by Riley against Murray was centred on three Tweets. The first Tweet was posted by Owen Jones on the 10th of January 2019. Owen Jones recalled an incident in which Nick Griffin, the former leader of the British National Party (BNP), was egged at a rally.

On the afternoon 3rd of March 2019, Jeremy Corbyn visited the Finsbury Park Mosque, which had previously been the site of a terrorist attack by right-wingers who had originally intended to target Corbyn himself. During the visit, Corbyn was attacked by a pro-Brexit campaigner who hit Corbyn over the head with an egg in his hand. The attack was reported in the media by 17:25.

Just over 45 minutes later, at 18:16, Riley posted what is referred to in Nicklin’s judgment as the ‘Good Advice’ Tweet. Riley tweeted:

Riley’s Tweet set Twitter aflame, as large numbers of users Tweeted support or condemnation of Riley’s Tweet. Owen Jones, for example, commented that Riley was ‘in the absolute gutter.’

At 21:07, Murray tweeted that:

Murray’s Tweet attracted significant attention, no doubt in part because Riley quote-tweeted Murray’s Tweet in order to condemn it just after midnight on the 4th of March. Following a flurry of Tweets attacking her, Murray deactivated her Twitter account at approximately 9AM.

Riley alleged that Murray had libelled her because she believed that Murray had misrepresented the true meaning of her Tweet. Riley claimed that the Tweet was actually aimed at illustrating the hypocrisy of the left, which celebrated Griffin’s egging but condemned Corbyn’s. Riley contended that she did not intend it to mean that Corbyn deserved to be attacked.

The Judgment

Murray responded to the allegations by submitting defences of substantial truth, honest opinion and public interest. Nicklin ultimately rejected all three defences, although the honest opinion and public interest defences failed because Nicklin rejected the truth defence. Thus, it is Nicklin’s determination on truth that sits at the heart of his judgment.

Murray’s defence was straightforward. In papers, she argued that argued that:

-

the Good Advice Tweet “(a) meant; (b) was capable of meaning; (c) was capable of being understood to mean; and/or (d) would have been understood to mean by some or all the people who read it, that Mr Corbyn deserved to be violently attacked” and that and that the meaning “substantially conveyed” by the Good Advice Tweet was that Mr Corbyn deserved to be violently attacked’ and/or

-

that it was reasonable for a reader of the Good Advice Tweet to understand and/or interpret it to mean that the Claimant was stating that Mr Corbyn deserved to be violently attacked.

Nicklin rejected this defence, but on unique and extremely strange grounds. Nicklin found that Riley’s Tweet was ambiguous and that there were ‘two obvious meanings’ to Riley’s Tweet: the ‘hypocrisy’ meaning that Riley maintained and the meaning suggested by Murray. However, Murray had stated categorically that the Tweet had one meaning, namely, the ‘Corybn-is-a-Nazi’ meaning, which erased the ambiguity of Riley’s Tweet:

She took upon herself the burden of describing, as a matter of fact, what the Claimant had said and failed because she removed the element of ambiguity.

The Problems with the Judgment

Nickin’s judgment is flawed on two primary grounds.

First, Nicklin’s judgment is remarkable for its failure to fully engage with the meaning of Riley’s Tweet, which should have been at the heart of his judgment. Indeed, Nicklin does not actually set about extracting the meaning of Riley’s Tweet at any stage during his discussion of the truth defence. Instead, Nicklin relies on the fact users on Twitter had interpreted the Tweet in multiple ways. On this basis, Nicklin determined that the Tweet was ambiguous and had at least two meanings.

However, Nicklin spends no time assessing whether these meanings were reasonable and obvious; which of the two meanings would have been most obvious to the average reader.

Arguably, Murray’s meaning was the more obvious because Murray’s understanding of Riley’s Good Advice tweet was literal. Murray believed that when Riley tweeted ‘Good Advice’ in relation to Corbyn’s attack (and Riley did not dispute she was talking about the attack on Corbyn in her Tweet), Riley meant that Jones’ advice was good and, because she was talking about Corbyn, should be applied to him too.

The hypocrisy meaning requires considerably more work to understand. The reader must understand that when Riley tweets ‘Good Advice’, the meaning is actually ‘Bad Advice.’ Moreover, the reader must make the additional leap of interpretation by coming to the conclusion that it is ‘Bad Advice’ because nobody (including Nazis) should be egged – not because the advice was selectively applied.

Second, Nicklin’s judgment has actually found Murray innocent on the facts, but has contorted matters into finding her guilty in law.

In libel law, there is a healthy debate about how to assess the meaning of a statement: whether the court should attempt to define a single meaning for a statement or whether the court should accept that a statement can have multiple meanings. This debate was comprehensively covered in the judgment of Justice Haddon-Cave in Shakeel Begg vs. BBC. Begg, as it is referred to in shorthand, is the go-to jurisprudence on this issue.

Another key part of libel law is that truth is the ultimate defence against libel. If somebody says something true, it cannot be libellous.

The importance of this debate is that, up until Nicklin’s judgment, Begg held that if a statement has multiple meanings, and the accused has interpreted it to mean one of those meanings, they would succeed a truth defence. Or, in other words, it would be substantially true if someone interpreted a statement which has two reasonable meanings in one of the reasonable ways. How the court establishes substantial truth is dealt with at paragraph 61 of the Begg judgment as follows:

The Court simply has to decide whether a section of the audience would reasonably take the words spoken to convey a particular message. Thus, if the Court were to conclude that at least a section of the audience would reasonably take the Claimant’s words to carry a particular message, that would be sufficient to support a finding that his words conveyed that message, even if it could not be said with certainty that the words were understood or conveyed the same message to everyone present.

At paragraph 155 of Nicklin’s judgment, he finds that there were ‘two obvious’ meanings that could be read from the Good Advice tweet – the hypocrisy and Corbyn-is-a-Nazi meaning.

Prior to Nicklin’s judgment, this would have secured Murray a successful truth defence. This is because Murray reflected one of the ‘two obvious’ meanings, which meant that what Murray tweeted was substantially true.

But Nicklin’s judgment has considerably altered the previous jurisprudence. He argues that it is not enough for a person to reflect one of the substantially true meanings of a statement. Instead, anybody responding to an ambiguous statement must find some way to reflect all of these meanings, or the ambiguity of the statement itself.

This aspect of Nicklin’s judgment is all the more striking because he found that Murray was both a truthful witness and was not acting maliciously in posting her Tweet. Murray, according to Nicklin’s determination, genuinely believed Riley’s Tweet to have the meaning that Murray gave it.

In comparison, Nicklin is critical of Riley. Not only did Nicklin attack Riley’s insistence at trial that Murray was acting maliciously, he also acknowledged that Riley’s Good Advice tweet was ‘provocative’ or ‘mischievous.’ Even more importantly, Nicklin found that Riley, herself, knew that ‘the Good Advice Tweet was capable of being read in both senses. She may have intended the first, but she was certainly not blind to the second.’

It is only at this point, at the very end of his judgment, that that Nicklin takes a faint stab at coming to his own understanding of Riley’s Tweet – and then pulls away from the implications of his own findings. Here, Nicklin notes that Riley had stated later on Twitter that ‘she had been speaking about anti-Semitism.’ Nicklin then comments that that ‘the Good Advice Tweet could only sensibly be regarded as concerning anti-Semitism if it was construed in the meaning of Jeremy Corbyn deserving to be egged because of his political views.’

So not only did Murray interpret the Tweet in a substantially true manner, she also did so in good faith. Riley, for her part, put out a provocative Tweet that she knew could be read in multiple ways. Riley, moreover, stated that the Good Advice Tweet was about anti-Semitism, which Nicklin belatedly acknowledges supports Murray’s interpretation of the Tweet.

And yet Nicklin still found Murray guilty.

The Implications of Nicklin’s Judgment

Nicklin’s judgment has substantially upended the straightforward and common sense jurisprudence in Begg . It is now no longer sufficient for somebody to report on a statement according to one of its reasonable meanings; they now have to reflect all its potential multiple meanings, or, at least, allude to the possibility of multiple meanings.

The possibility for abuse is obvious. An individual could purposefully post a controversial, ambiguous Tweet on Twitter, in anticipation that people will interpret it in one way or another, giving rise to a potentially ruinous libel claim against an individual who takes it to have a certain meaning, even if taking that meaning was reasonable.

It is striking that Nicklin found that Riley was perfectly aware that her Tweet could be interpreted in multiple ways – and yet awards Riley damages because Murray interpreted the Tweet in one of those substantially true ways.

The scale for abuse is widened because Nicklin has also taken a potentially dangerous approach to establishing meaning. Following Nicklin’s approach, it appears that all that needs to be done to establish that a Tweet or statement has an ambiguous meaning is to show that a handful of people held it to have more than one meaning. In the abuse scenario, it is, again, easy to imagine a handful of collaborators posting Tweets reflecting a particular meaning, precisely with the aim of creating the case for ambiguity. Nicklin, himself, spends no real time assessing the meaning of Riley’s Tweet in any great depth, or explaining which of the two meanings of Riley’s Tweet was more natural or obvious.

Nicklin’s judgment also imposes a common sense inversion of where responsibility lies in the act of communicating between two parties. It seems obvious that if a person doesn’t want to be misunderstood, they must communicate clearly. Under Nicklin’s version, however, it is the reader that must attempt to parse out all possible meanings of an ambiguous and unclear statement; and that, if they fail to do so, they could face financial ruin in the courts.

In a country where libel is overwhelmingly used to close down debate and defend the rich and powerful, any decision that extends the reach and applicability of libel law is concerning. But is particularly concerning when the law now imposes requirements on the average Twitter user that go far beyond what has ever existed before, and which opens good faith actors to libel claims for the crime of interpreting an ambiguous statement in a reasonable way.

XMC.PL

June 24, 2022 at 8:59 am

I do agree with all the ideas you have presented in your post. Theyre very convincing and will certainly work. Still, the posts are very short for newbies. Could you please extend them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.